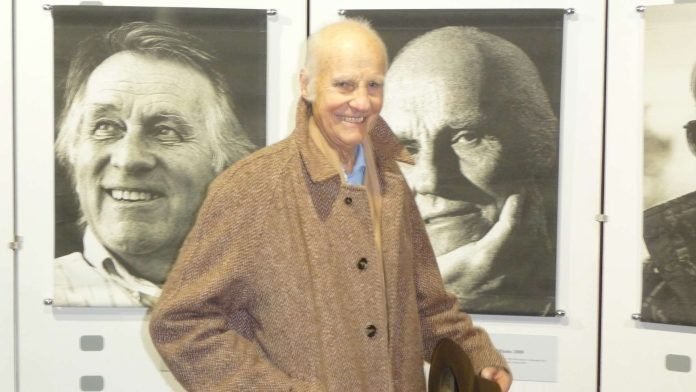

1929-2025

Details of Billy’s funeral can be found here

Billy Williams BSC, Oscar-nominee for Women In Love and On Golden Pond, Oscar-winner for Ghandi in 1982, and Camerimage Lifetime Achievement winner in 2000, has sadly passed away.

Williams himself grew up in what he describes as an atmosphere of filmmaking. His father, Billie Williams, started in the business as an apprentice in 1910, and during World War I served in the Royal Navy, being among the cameramen who filmed the surrender of the German fleet at Scapa Flow. After the war Williams senior resumed his career in film, shooting documentaries and expeditions.

Williams junior was born in 1929 and, on leaving school at the age of 14, had the choice of becoming his father’s apprentice or going into the Stock Exchange. He chose film and, after several years with his father, did his National Service in the RAF, where he yearned for greater independence in his work as a cameraman. On leaving the RAF he joined British Transport Films and spent five years travelling around the UK as a camera assistant, filming railways, canals and docks.

Anxious to become a documentary cameraman in his own right, Williams invested in his own equipment, common practice at the time as there were no equipment rental houses. “To me, the camera was almost part of the family,” he says. His first camera was an ARRI 2B with Cooke lenses, and from the mid 1950s to the early 1960s Williams worked on documentary films.

The growth of television advertising led to his next move, joining a new company making commercials. It was at this time he made the transition to being a lighting cameraman, although he dislikes the term, calling it “an unfortunate label”. Deeming the American favoured title director of photography “a bit grand”, Williams prefers cinematographer, particularly as the root, kinemat, means motion and he sees himself as a photographer of movement.

What was meant to be only a few days work in TV commercials continued for six years. During this period he learned about lighting. Williams sees this as the key to filming people, which he believes to be the most important aspect of cinematography.

“You’ve got to get the right atmosphere,” he acknowledges, “and you can get that by working with the director, but how people look is very important. It’s not portraiture, always making people look their best, because at times the story calls for them to look older, or more threatening, and that can be achieved by directing the lighting and integrating colour.”

Williams won praise for his photography of snowy Finnish landscapes and steel-blue skies on Billion Dollar Brain (1967), the first big budget, high profile feature he shot after a couple of low budget films. It was the first film he made with director Ken Russell, with whom he had shot a number of commercials. After the first choice cinematographer refused to take a medical, Russell asked for Williams and the two went on to make Women In Love (1969). Williams received an Academy Award nomination for this and he rates it among his personal favourites, particularly for the innovative lighting during the infamous naked wrestling scene.

Many directors and cinematographers form teams and make a series of films together. Williams and Russell may have done this but Williams passed on the The Devils (1971) and the two did not work together again until 1989’s The Rainbow. Russell was nonetheless fulsome in praise of Williams in his autobiography, saying that the cinematographer had enhanced his reputation in the interim. During those years Williams worked with John Schlesinger, Mark Rydell, Guy Green, Richard Attenborough and Peter Yates, directors he feels he shared experiences with and helped to capture their visions.

Rydell’s film On Golden Pond (1981) is another personal highlight, both for working with Katherine Hepburn and for the effort that went into lighting the house by the lake. The heavily wooded surroundings meant that Williams had to create each time of day seen through the windows, which brought him another Academy nomination. Through his career Williams has been nominated several times for BAFTA and BSC awards and in 1982 won the Academy Award for Best Cinematography for Gandhi. In 2000 his work was recognised with the Lifetime Achievement Award at the Camerimage Festival in Poland, an event that Williams rates highly and continues to attend. The following year he received the ASC’s International Award.

Since retiring from shooting in 1996, Williams has kept in touch with the business he obviously still has great enthusiasm for by attending industry events and lecturing at the National Film and Television School (NFTVS). He first lectured there in 1978 and has returned two to three times a year ever since. On the day we met at the NFTVS Williams was preparing for a seminar involving digital projection, a technology he regards as still in its early stages.

Working with digital has required cinematographers to be more involved in the post-production process, which has caused concern in the business because producers are not prepared to pay for the extra work.

“The studios rely on our expertise both on set and in post, because very often the director is inexperienced, so they should pay for it,” Williams observes. He advises upcoming cinematographers to negotiate contracts that have such a proviso. He is also concerned about long working hours on today’s features, recalling the days when studios were run almost on office hours.

Billy Williams is an avowed lover of film as a medium, describing the difference between it and high definition as the difference between leather and plastic. While his career was built on his visual sense, Williams says he has always been interested in strong storylines and character development and so was not tempted to make the jump to directing, which might have meant action pictures.

“I was happy in what I was doing,” he says. The feeling is that with a distinguished career not far behind him, the opportunity to teach aspiring cinematographers and more time to spend with his family, he would not want to change a thing.

FILMOGRAPHY

San Ferry Ann, dir: Jeremy Summers 1965

Red and Blue, dir: Tony Richardson 1966

Just Like a Woman, dir: Robert Fuest 1966

30 is a Dangerous Age, Cynthia, dir: Joe McGrath 1966

Billion Dollar Brain, dir: Ken Russell 1967

The Magus, dir: Guy Green 1968

Women In Love, dir: Ken Russell 1969

Two Gentlemen Sharing, dir: Alan Cooke 1970

Sunday, Bloody Sunday, dir: John Schlesinger 1971

Tam-Lin, dir: Roddy McDowall 1972

Zee & Co, dir: Brian Hutton 1972

Pope Joan, dir: Michael Anderson 1972

Kid Blue, dir: James Frawley 1973

Night Watch, dir: Brian Hutton 1973

Glass Menagerie (TV), dir: Antony Harvey 1973

The Exorcist (Iraq sequence), dir: William Friedkin 1973

A Likely Story, dir: William Kronick 1974

The Wind and the Lion, dir: John Milius 1975

Voyage of the Damned, dir: Stuart Rosenberg 1976

The Devil’s Advocate, dir: Guy Green 1978

The Silent Partner, dir: Daryl Duke 1978

Going in Style, dir: Martin Brest 1979

Boardwalk, dir: Stephen Verona 1979

Eagle’s Wing, dir: Anthony Harvey 1979

Saturn 3, dir: Stanley Donen 1980

On Golden Pond, dir: Mark Rydell 1981

Monsignor, dir: Frank Perry 1982

Gandhi, dir: Richard Attenborough 1982

The Survivors, dir: Michael Ritchie 1983

Ordeal by Innocence, dir: Desmond Davis 1984

Eleni, dir: Peter Yates 1985

Dreamchild, dir: Gavin Millar 1985

The Manhattan Project, dir: Marshall Brickman 1986

Suspect, dir: Peter Yates 1987

Just Ask for Diamond, dir: Stephen Bayley 1988

The Rainbow, dir: Ken Russell 1989

Stella, dir: John Erman 1989

Shadow of the Wolf, dir: Jacques Dorfmann 1992

Reunion, dir: Lee Grant 1994

Driftwood, dir: Ronan O’Leary 1996